Low Back Pain and Neurological Balance

The Morning Shower

The typical morning shower is neither 100% cold water nor 100% hot water, but rather a balance of the two. The perfect shower water temperature is a balance of hot and cold water.

While enjoying the perfect shower, if suddenly the hot water is turned drastically higher, the brain perceives:

Ouch! The water is too hot!

In this situation, the cold water is where it is supposed to be, but the hot water is too high. Hot and cold are no longer in balance. The ouch suggests the experience is painful. [Remember, pain and temperature share the same neurological pathway to the brain]. The most common remedy is to quickly turn down the hot water to reestablish balance.

Pain in General

Most pain is an inflammatory event. Inflammatory chemicals irritate pain nerves. The understanding of the inflammatory chemical nature of pain was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1982 (1).

In 2007, the journal Medical Hypothesis expands and elaborates on the relationship between pain and inflammation. The article is titled (2):

The Biochemical Origin of Pain:

The Origin of all Pain is Inflammation and the Inflammatory Response: Inflammatory Profile of Pain Syndromes

The author states:

“Every pain syndrome has an inflammatory profile consisting of the inflammatory mediators that are present in the pain syndrome.”

“The key to treatment of Pain Syndromes is an understanding of their inflammatory profile.”

“Our unifying theory or law of pain states: the origin of all pain is inflammation and the inflammatory response.”

“Irrespective of the type of pain whether it is acute or chronic pain, peripheral or central pain, nociceptive or neuropathic pain, the underlying origin is inflammation and the inflammatory response.”

“Activation of pain receptors, transmission and modulation of pain signals, neuro-plasticity and central sensitization are all one continuum of inflammation and the inflammatory response.”

“Irrespective of the characteristic of the pain, whether it is sharp, dull, aching, burning, stabbing, numbing or tingling, all pain arises from inflammation and the inflammatory response.”

Using our shower metaphor, inflammation is hot water. “Turning down the hot water” of pain perception is most commonly done by using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or by using other anti-inflammatory drugs such as steroids. This approach seems logical, but there are problems:

In 2003, the journal Spine states (3):

“Adverse reactions to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) medication have been well documented.”

“Gastrointestinal toxicity induced by NSAIDs is one of the most common serious adverse drug events in the industrialized world.”

There is “insufficient evidence for the use of NSAIDs to manage chronic low back pain, although they may be somewhat effective for short-term symptomatic relief.”

In 2006, the journal Surgical Neurology states (4):

“More than 70 million NSAID prescriptions are written each year, and 30 billion over-the-counter NSAID tablets are sold annually.”

“5% to 10% of the adult US population and approximately 14% of the elderly routinely use NSAIDs for pain control.”

Almost all patients who take the long-term NSAIDs will have gastric hemorrhage, 50% will have dyspepsia, 8% to 20% will have gastric ulceration, 3% of patients develop serious gastrointestinal side effects, which results in more than 100,000 hospitalizations, an estimated 16,500 deaths, and an annual cost to treat the complications that exceeds 1.5 billion dollars.

“NSAIDs are the most common cause of drug-related morbidity and mortality reported to the FDA and other regulatory agencies around the world.”

One author referred to the “chronic systemic use of NSAIDs to ‘carpet-bombing,’ with attendant collateral end-stage damage to human organs.”

In 2017 and 2019, cardiologist Steven Gundry, MD, explains how the consumption of NSAIDs disrupts the integrity of the gut protective mucus membrane, increasing adverse gut permeability (“leaky gut”), increasing one’s systemic inflammation and hence increasing pain. Dr. Gundry states (2017) (5):

“Copious research published over the last half century reveals that gulping down apparently harmless NSAIDs is like swallowing a live grenade. These drugs blow gaping holes in the mucus-lined intestinal barrier.”

“As a result, lectins, lipopolysaccharides, and living bacteria are able to deluge the breaks in your levee, flooding your body with foreign invaders.”

“Inundated by these foreign proteins and other invaders, your immune system does what if does best, producing inflammation and pain. This pain in turn prompts you to down another NSAID, promoting a vicious cycle.” “... the more pain you have, the more NSAIDs you take.”

“Increased intestinal permeability from ... the regular use of NSAIDs and acid-reducing drugs, pro¬duces what is commonly called leaky gut syndrome.”

“NSAIDs are both the number-one pharmaceutical seller and the number-one health menace.”

In addition to these (and many other) side effect problems from the consumption of NSAIDs, there is another major concern. These anti-inflammatory drugs are not very effective, especially for chronic pain problems (17). If these drugs worked well, Americans would not need to fill 70 million prescriptions and consume 30 billion over-the-counter NSAID tablets yearly.

Low Back Pain Paradigm Shift

Drugs for the management of low back pain, especially for chronic low back pain, have sufficient down-sides. Consequently, in recent years, low back pain management and guidelines have advocated not using drugs but rather to use non-pharmacological approaches (7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13).

Return to the Shower, A Different Model

While enjoying the perfect shower, there is another method of creating the perception of too hot and/or pain: turn off the cold water. An interesting corollary is the understanding that the hot water is at the perfect level. The problem, the imbalance, is a lack of cold water. Yet, the brain perception of hot/pain is the same, ouch!

The remedy is not to turn down (or off) the hot water because the hot water is where it is supposed to be. Rather, the remedy is to turn up the cold water.

Why Do Patients Go to Chiropractors?

By a significant percentage, the primary reason patients go to chiropractors is for the management of low back pain (14). The actual number is 63%. Many of these patients have already taken over-the-counter or prescription NSAIDs, with less than acceptable clinical improvement.

Chiropractic spinal adjusting (specific spinal manipulation) is both safe and very successful for these patients (15, 16, 17, 18, 19).

What Tissue is the Primary Source of Chronic Low Back Pain?

The primary tissue responsible for chronic low back pain is the intervertebral disc (20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27). It has been documented for decades that the intervertebral disc is innervated with nociceptors [hot water], and that inflammatory chemicals in the disc increases the depolarization of the disc nociceptors.

What if, as is often the case, the patient has been taking NSAIDs, but the clinical improvement is unacceptable? Perhaps their pain persists because the cold water has been turned down or off. In such a case, the solution is to turn the cold water up, reestablishing balance.

What Nerves Function as the Cold Water?

In our model, the hot water represents the nociceptors (pain afferents). What represents the cold water? It is mechanical nerves that are also in the intervertebral disc.

These mechanical nerves are referred to proprioceptors or mechanoreceptors. When spinal joints do not move appropriately, the mechanoreceptors [cold water] are turned down or perhaps turned off, leaving the nociceptors [hot water] unopposed. The result is pain, even though the nociceptors are actually functioning normally. There is an imbalance between the hot and cold water.

What is the Gate Theory of Pain?

The Gate Theory of Pain was proposed in 1965 by Ronald Melzack and Patrick Wall (28), and it has survived in depth scientific scrutiny and the test of time (29). It was reviewed and applied to chiropractic spinal adjusting by Canadian orthopedic surgeon William H. Kirkaldy-Willis, MD, in 1985 (30).

Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis notes that Melzack and Wall’s Gate Theory of Pain, has “withstood rigorous scientific scrutiny.” He further states:

“The central transmission of pain can be blocked by increased proprioceptive input.” Pain is facilitated by “lack of proprioceptive input.” This is why it is important for “early mobilization to control pain after musculoskeletal injury.”

“Increased proprioceptive input in the form of spinal mobility tends to decrease the central transmission of pain from adjacent spinal structures by closing the gate. Any therapy which induces motion into articular structures will help inhibit pain transmission by this means.”

Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis’ discussion of the Gate Theory of Pain involves the “closing” of the pain gate through the enhancement of proprioception (mechanoreception). Spinal manipulation improves the movement parameters of articulations. The improvement of joint motion results in a neurological sequence of events that “closes” the pain gate.

In our model, spinal adjusting would turn up the cold water, reestablish balance with the hot water, and balance (eliminate) pain perception in the brain.

Is There Evidence that Proprioceptors/Mechanoreceptors (cold water)

Exist in the Intervertebral Disc?

Melzack and Wall’s Gate Theory of Pain was published in 1965. Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis’ article on chiropractic spinal manipulation and the Gate Theory of Pain was published in 1985. Since 1985, a number of studies have investigated the anatomy and physiology of joint mechanoreceptors, often using human subjects. Several of these are presented here:

In 1992, the journal Spine published a study titled (31):

Neural Elements in Human Cervical Intervertebral Discs

The authors note:

- The intervertebral disc is innervated with mechanoreceptors, [cold water] perhaps as deep as to the nucleus pulposus.

- These mechanoreceptors communicate to the central nervous system, providing basic proprioceptive function, including the sense of compression, deformation, and alignment. They state:

“The presence of neural elements within the intervertebral disc indicates that the mechanical status of the disc is monitored by the central nervous system.”

“The location of the mechanoreceptors may enable the intervertebral disc to sense peripheral compression or deformation as well as alignment.”

In 1995, the journal Spine published a study titled (32):

Mechanoreceptors in Intervertebral Discs:

Morphology, Distribution, and Neuropeptides

The authors documented the occurrence and morphology of

mechanoreceptors in human intervertebral discs. They found that the lumbar intervertebral discs are innervated with mechanoreceptors, and that once again these mechanoreceptors provide basic proprioceptive function, including the maintenance of muscle tone and muscular reflexes. They state:

Physiologically, these mechanoreceptors “provide the individual with sensation of posture and movement.”

“In addition to providing proprioception, mechanoreceptors are thought to have roles in maintaining muscle tone and reflexes.”

“Their presence in the intervertebral disc and longitudinal ligament can have physiologic and clinical implications.”

In 2010, the Journal of Clinical Neuroscience published a study titled (33):

An Immunohistochemical Study of Mechanoreceptors

in Lumbar Spine Intervertebral Discs

This study used twenty-five lumbar (L4–5 and L5–S1) fresh human

intervertebral discs. Again, these lumbar intervertebral discs were

innervated with mechanoreceptors.

These mechanoreceptors are important in maintaining proper muscle

tone and when dysfunctional can create intense muscle spasms. They also

provide basic proprioceptive function, specifically the sense of compression, deformation, kinesthesia, and alignment. These authors state:

“These receptors have a key role in the perception of joint position and adjustment of the muscle tone of the vertebral column.”

“An important component of low back pain is an intense muscle spasm of the vertebral musculature, elicited through reflex arches mediated by specialized nerve endings.”

“During axial loading of a motion segment, compressive stresses in the nucleus will generate tensile stresses in the peripheral annulus, which is rich in neural receptors.”

“In conclusion, this study confirms the existence of an abundant network of encapsulated and non-encapsulated receptors in the intervertebral discs of the lower lumbar spine in normal human subjects. The principal role of encapsulated structures is assumed to be the continuous monitoring of position, velocity and acceleration (kinesthesia).”

What is the Optimal Anatomical Balance Between Nociceptors (Hot Water) and Mechanoreceptors (Cold Water) in the Intervertebral Disc?

The answer is unknown, but a study was published in 2012 suggesting that 24% of the neurofilaments in the intervertebral disc are nociceptors and 56% are mechanoreceptors. This would suggest, rounded, that there should be twice as much cold water (mechanoreceptors) as hot water (nociceptors) (34).

What Can Cause an Anatomical Imbalance

Between the Number of Nociceptors v. Mechanoreceptors?

Why Is Disc Degenerative Disease So Often

Associated with Chronic Low Back Pain?

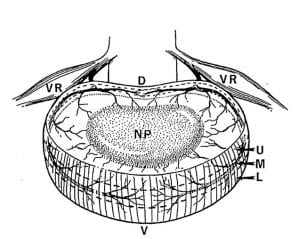

The intervertebral disc (IVD) is composed of three main anatomical regions:

- The central nucleus pulposus (NP):In the normal IVD, the NP is both avascular and aneural (void of both blood supply and nerves).

- The annulus fibrosus (AF): In the normal IVD, the NP is avascular, but the outer third or so of the AF is innervated with nerves, including nociceptors (hot water) and mechanoreceptors (cold water).

- The cartilaginous endplate (CEP): In the normal IVD, the CEP is both vascular and has nerves. AF and NP nutrition (and hence health) is dependent upon movement through the porous CEP, which itself is dependent upon motor unit movement (23).

Disc Degeneration has multiple causes:

- Genetics

- Age

- Smoking

- Glycating Diets (high carbohydrate consumption)

- Injury (either macro or repetitive micro events)

- Weight

- Load

- Reduced motion

- Reduced blood supply to the vertebral body cartilaginous end plates

- Inadequate nutrient supply

- Infection

- Autoimmune cascades

- Combinations of multiple of these factors

When the disc degenerates, more often than not it changes its anatomical innervation. This phenomenon is called:

Hyperinnervation, Neoneuralisation, Receptive Field Enlargement

Neoneuralisation was first described in 1997 and has been confirmed by many subsequent investigations (35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41). The nerves that are normally located only in the outer annulus fibrosis migrate into the inner annulus and even into the nucleus pulposus. As noted above, both the inner annulus and even the nucleus pulposus are normally without nerves.

The titles alone of these publications tell a story:

Nerve Ingrowth into Diseased Intervertebral Disc in Chronic Back Pain (35), 1997

Innervation of “Painful” Lumbar Discs (36), 1997

Nerve Growth Factor Expression and Innervation of the Painful Intervertebral Disc (37), 2002

Increased Nerve and Blood Vessel Ingrowth Associated with Proteoglycan Depletion in an Ovine Annular Lesion Model of Experimental Disc Degeneration (38), 2002

The Pathogenesis of Discogenic Low Back Pain (39), 2005

Annulus Fissures Are Mechanically and Chemically Conducive to the Ingrowth of Nerves and Blood Vessels (40), 2012

Nerves are More Abundant Than Blood Vessels in the Degenerate Human Intervertebral Disc (41), 2015

Initially (23 years ago, 1997), the concept that nerves could migrate from the outer annulus of the IVD into the inner annulus and even nucleus pulposus was met with much skepticism. Today, there are many investigational studies that document this phenomenon. These studies are somewhat different investigational methods, are done by different groups in universities throughout the world and published in various respected journals. This constitutes convergent validity.

Despite this documentation, most health care providers, including those that specialize in treating back pain, are unfamiliar with it, and often deny its existence.

Histologically (looking at tissues through microscopes and often with the use of specific staining technology), different categories of nerves appear different from each other. Histological assessment can distinguish nociceptors (hot water) from mechanoreceptors (cold water).

Interestingly and startling, the new nerves into the inner regions of the disc are classified as nociceptors. More nociceptors without more mechanoreceptors. Hence, beginning more than two decades ago, a unique explanation for back pain and chronicity began to emerge: more pain nerves grow into the disc, and without mechanoreceptors.

The clinical relevance is that this neuroanatomical aspect of chronic low back pain perception complicates matters for both the patient and the doctor. Even minor mechanical dysfunction may result in pain perception. This may be the explanation for why some patients require mechanical care (chiropractic adjusting) at a greater frequency that others, and why home mechanical care (exercise, blocking, pulleys, etc.) is more necessary for some chronic patients than others.

This explanation for chronic low back pain also underscores the concerns of long-term drugs for symptom control and would support the reason for long-term ongoing mechanical care.

REFERENCES:

- http://www.nobelprize.org

- Omoigui S; The biochemical origin of pain: The origin of all pain is inflammation and the inflammatory response: Inflammatory profile of pain syndromes; Medical Hypothesis; 2007; Vol. 69; pp. 1169–1178.

- Giles LGF; Reinhold Muller R; Chronic Spinal Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation; Spine; July 15, 2003; Vol. 28; No. 14; pp. 1490-1502.

- Maroon JC, Bost JW; Omega-3 Fatty acids (fish oil) as an anti-inflammatory: An alternative to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for discogenic pain; Surgical Neurology; April 2006; Vol. 65; pp. 326–331.

- Gundry S; The Plant Paradox: The Hidden Dangers in “Healthy” Foods that Cause Disease and Weight Gain; Harper Wave; 2017.

- Gundry S; The Longevity Paradox: How to Die Young at a Ripe Old Age; Harper Wave 2019.

- Ghildayal N, Johnson PJ, Evans RL, Kreitzer MJ; Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use in the US Adult Low Back Pain Population; Global Advances in Health and Medicine; January 2016; Vol. 5; No. 1; pp. 69-78.

- Roger Chou, MD; Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MHA; Vincenza Snow, MD; Donald Casey, MD, MPH, MBA; J. Thomas Cross Jr., MD, MPH; Paul Shekelle, MD, PhD; and Douglas K. Owens, MD, MS; Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain; Annals of Internal Medicine; Vol. 147; No. 7; October 2007; pp. 478-491.

- Roger Chou, MD, and Laurie Hoyt Huffman, MS; Non-pharmacologic Therapies for Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain; Annals of Internal Medicine; October 2007; Vol. 147; No. 7, pp. 492-504.

- Globe G, Farabaugh RJ, Hawk C, Morris CE, Baker G, DC, Whalen WM, Walters S, Kaeser M, Dehen M, DC, Augat T; Clinical Practice Guideline: Chiropractic Care for Low Back Pain; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; January 2016; Vol. 39; No. 1; pp. 1-22.

- Wong JJ, Cote P, Sutton DA, Randhawa K, Yu H, Varatharajan S, Goldgrub R, Nordin M, Gross DP, Shearer HM, Carroll LJ, Stern PJ, Ameis A, Southerst D, Mior S, Stupar M, Varatharajan T, Taylor-Vaisey A; Clinical practice guidelines for the noninvasive management of low back pain: A systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration; European Journal of Pain; Vol. 21; No. 2 (February); 2017; pp. 201-216.

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA; Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians; For the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians; Annals of Internal Medicine; April 4, 2017; Vol. 166; No. 7; pp. 514-530.

- Abbasi J; Researching Nondrug Approaches to Pain Management; An Interview with Robert Kerns, PhD; Journal of the American Medical Association; March 28, 2018; E1.

- Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Moore C; The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults; Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey; Spine; December 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 23; pp. 1810–1816.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985; Vol. 31; pp. 535-540.

- Meade TW, Dyer S, Browne W, Townsend J, Frank OA; Low back pain of mechanical origin: Randomized comparison of chiropractic and hospital outpatient treatment; British Medical Journal; June 2, 1990; Vol. 300; pp. 1431-1437.

- Giles LGF, Muller R; Chronic Spinal Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation; Spine; July 15, 2003; Vol. 28; No. 14; pp. 1490-1502.

- Muller R, Giles LGF; Long-Term Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial Assessing the Efficacy of Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation for Chronic Mechanical Spinal Pain Syndromes; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; January 2005; Vol. 28; No. 1

- Coulter ID, Crawford C, Hurwitz EL, Vernon H, Khorsan R, Booth MS, Herman PM; Manipulation and Mobilization for Treating Chronic Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis; The Spine Journal; May 2018; Vol. 18; No. 5; pp. 866-879.

- Smyth MJ, Wright V, Sciatica and the intervertebral disc. An experimental study; Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery [American]; Vol. 40; No. 1548; pp. 1401-1408.

- Bogduk N, Tynan W, Wilson A. S., The nerve supply to the human lumbar intervertebral discs; Journal of Anatomy; 1981; Vol. 132; No. 1; pp. 39-56.

- Bogduk N; The innervation of the lumbar spine; Spine; April 1983; Vol. 8; No. 3; pp. 286-293.

- Mooney V; Where Is the Pain Coming From?; October 1987; Spine; Vol. 12; No. 8; pp. 754-759.

- Kuslich S, Ulstrom C, Michael C; The Tissue Origin of Low Back Pain and Sciatica: A Report of Pain Response to Tissue Stimulation During Operations on the Lumbar Spine Using Local Anesthesia; Orthopedic Clinics of North America; Vol. 22; No. 2; April 1991; pp.181-187.

- Faustmann PM; Neuroanatomic basis for discogenic pain; Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb; Nov-Dec 2004; Vol. 142; No. 6; pp. 706-708. [Article in German]

- Ozawa T, Ohtori S, Inoue G, Aoki Y, Moriya H, Takahashi K; The Degenerated Lumbar Intervertebral Disc is Innervated Primarily by Peptide-Containing Sensory Nerve Fibers in Humans; Spine; October 1, 2006; Vol. 31; No. 21; pp. 2418-2422.

- Bogduk N, Aprill C, Derby R; Lumbar Discogenic Pain: State-of-the-Art Review; Pain Medicine; June 2013; Vol. 14; No. 6; pp. 813–836.

- Melzack R, Wall P; Pain mechanisms: a new theory; Science; November 19, 1965; Vol. 150; No. 3699; pp. 971-979.

- Dickenson AH; Gate Control Theory of Pain Stands the Test of Time; British Journal of Anaesthesia; June 2002; Vol. 88; No. 6; pp. 755-757.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985; Vol. 31; pp. 535-540.

- Mendel T, Wink CS, Zimny ML; Neural elements in human cervical intervertebral discs; Spine; February 1992; Vol. 17; No. 2; pp. 132-135.

- Roberts S, Eisenstein SM, Menage J, Evans EH, Ashton IK; Mechanoreceptors in intervertebral discs: Morphology, distribution, and neuropeptides; Spine; December 15, 1995; Vol. 20; No. 24; pp. 2645-51.

- Dimitroulias A, Tsonidis C, Natsis K, Venizelos I, Djau SN, Tsitsopoulos P; An immunohistochemical study of mechanoreceptors in lumbar spine intervertebral discs; Journal of Clinical Neuroscience; June 2010; Vol. 17; No. 6; pp. 742-745.

- Fujimoto K, Miyagi M, Ishikawa T, Inoue G, and 16 more; Sensory and Autonomic Innervation of the Cervical Intervertebral Disc: The Pathomechanics of Chronic Discogenic Neck Pain; Spine; July 15, 2012; Vol. 37; No. 16; pp. 1357–1362.

- Freemont AJ, Peacock TE, Goupille P, Hoyland JA, O’Brien J, Jayson MI; Nerve ingrowth into diseased intervertebral disc in chronic back pain; Lancet; Jul 19, 1997; Vol. 350; No. 9072; pp. 178-81.

- Coppes MH, Marani E, Thomeer RT, Groen GJ; Innervation of “painful” lumbar discs; Spine; October 15, 1997; Vol. 22; No. 20; pp. 2342-2349.

- Freemont AJ, Watkins A, Le Maitre C, Baird P, Jeziorska M, Knight MT, Ross ER; O’Brien JP, Hoyland JA; Nerve growth factor expression and innervation of the painful intervertebral disc; Journal of Pathology; July 2002; Vol. 197; No. 3; pp. 286-92.

- Melrose J, Roberts S, Smith S, Menage J, Ghosh P; Increased nerve and blood vessel ingrowth associated with proteoglycan depletion in an ovine annular lesion model of experimental disc degeneration; Spine; June 15, 2002; Vol. 15; No. 12; pp. 15; pp. 1278-1285.

- Peng B, Wu W, Hou S, Zhang C, Li P, Yang Y; The pathogenesis of discogenic low back pain; Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Br); January 2005; Vol. 87-B; No. 1; 62-67.

- Stefanakis M, Al-Abbasi M, Harding I; Pollintine P, Dolan P, Tarlton J, Adams MA; Annulus Fissures Are Mechanically and Chemically Conducive to the Ingrowth of Nerves and Blood Vessels; Spine; October 15, 2012; Vol. 37; Number 22; pp. 1883–1891.

- Binch ALA, Cole AA, Breakwell LM, Michael ALR, Chiverton N, Creemers LB, Cross AK, Le Maitre CL; Nerves are More Abundant Than Blood Vessels in the Degenerate Human Intervertebral Disc; Arthritis Research & Therapy; December 2015; Vol. 17:370.

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C.. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”