The Intersecting of Two Lives:

They Forever Improved Our Understanding of Back Pain

Architectural Mechanical History

For thousands of years, pyramids have been known around the globe: the Middle East, Asia, India, China, the Americas, etc. Also known for millennia are the architectural wonders of Greece, Rome, and the churches/cathedrals throughout Europe and Asia. When viewing these wonders, one questions, how was any of this possible? These marvels were constructed without the benefits of electricity, power tools, light bulbs, gasoline, cranes, calculators, computers, efficient supply chains, etc. The laborers did not benefit from the modern understanding of treatment for disease and/or injury, sanitation, reliable clean water, access to optimum nutrition, etc. Yet, their work product remains for all to see.

The basic understanding of architectural mechanics dates back thousands of years. Yet, on occasion, an architectural mechanical mishap will occur.

Pisa, Italy, has its notorious “Leaning Tower.” Groundbreaking for the Leaning Tower of Pisa was in the year 1173, and it was completed in 1372. The angle of the lean was 4 degrees and has increased over the centuries, putting the tower at risk of falling over.

The Millennium Tower is located in downtown San Francisco, California. It is a 58-story skyscraper. It was opened in 2009. In 2016, residences were informed that the building was progressively tilting. Cracking noted in 2018 alarmed everyone that a serious mechanical problem existed; the lean distance from the roof was 18 inches. By 2022, the lean had increased to 28 inches. Stabilization solutions are not easy, inexpensive, or guaranteed.

The message is simple yet critical: the most important mechanical concept in construction is to have a solid base, a solid foundation.

Buildings are solely mechanical. When a building leans too far, it risks falling over. In contrast, upright human posture is not solely mechanical. When humans tilt in any direction during the activities of life (posture, ergonomics, work-leisure activities, etc.), falling over rarely occurs. Human upright posture is biomechanical.

Levers

Upright human posture is a first-class lever mechanical system (1, 2). When humans lean (tilt), in any direction, muscles contract in a manner to counter-balance the lean, thus keeping the human upright (1, 2).

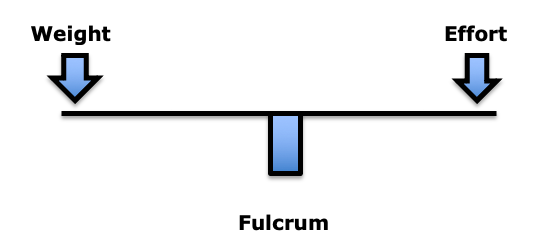

The first-class lever mechanical system has three components:

- Weight

- Fulcrum

- Effort

In the first-class lever mechanical system, the fulcrum is between the weight and the effort. The fulcrum is the site of greatest mechanical stress.

In the first-class lever mechanical system, the fulcrum is between the weight and the effort. The fulcrum is the site of greatest mechanical stress.

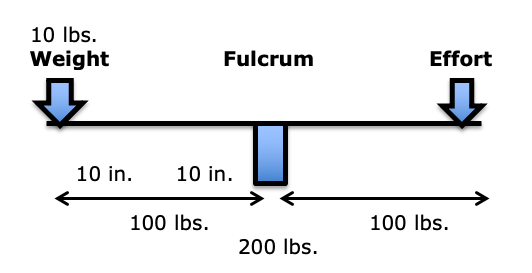

In this model, weight is important. But, more important than weight is the distance the weight is from the fulcrum. This is load (3). To maintain upright posture, the load must be counterbalanced by effort on the opposite side of the fulcrum. This effort is supplied by muscle contraction. For example:

If the weight is 10 lbs., and the distance from the fulcrum was 10 inches (the lever arm), the load on the fulcrum would be 100 lbs. (10 X 10). In order to remain balanced, the effort (muscle contraction) on the opposite side of the fulcrum would have to also be 100 lbs. The effective total load applied to the fulcrum would be 200 lbs. Thus, an actual weight of 10 lbs. would have an effective load on the fulcrum of 200 lbs.

In summary, the load experienced at the fulcrum of a first-class lever system is dependent upon three factors:

- The magnitude of the weight

- The distance the weight is away from the fulcrum (lever arm)

- The addition of the counterbalancing muscle effort required to remain balanced

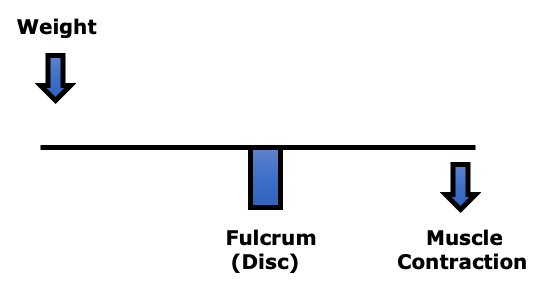

In the low back, the fulcrum of the first-class lever of upright posture is primarily the intervertebral disc. In the low back, the facet joints bear very little weight (4). In the low back, postural distortions primarily affect the lumbar spine intervertebral discs.

In their 1990 book Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine (1), Augustus White, MD, and Manohar Panjabi, PhD, state:

“The load on the discs is a combined result of the object weight, the upper body weight, the back-muscle forces, and their respective lever arms to the disc center.”

In her book Move Your DNA: Restore Your Health Through Natural Movement, biomechanist Katy Bowman clearly explains the difference between weight and load, emphasizing that the real problem is the load, which is the weight multiplied by a lever distance from a fulcrum, and of course adding the counter-balancing efforts of muscles. She states (3):

“The loads created by gravity depend upon our physical position relative to the gravitational force.”

The load created by gravity differs depending on alignment with the “perpendicular force of gravity.”

“Every unique joint configuration, and the way that joint configuration is positioned relative to gravity, and every motion created, and the way that motion was initiated, creates a unique load that in turn creates a very specific pattern of strain in the body.” This is called “load profile.”

“It’s not the weight that breaks you down, it’s the load created by the way you carry it.”

“Loads are often oversimplified to ‘weight’ because it makes them easier to understand, but there is much more going on with your sore knee (or foot, or back, or pelvic floor) than your weight.”

“Weight is not the be-all and end-all of loads. When you want to improve your health, it’s much more important to consider how you carry your weight than to spend hours contemplating the lone data point that is Your Weight.”

The Intervertebral Disc

(the fulcrum)

The primary reason people seek chiropractic care is for chronic low back pain (5). Studies indicate that chronic low back pain is primarily discogenic (6, 7, 8, 9, 10). It is also understood that the intervertebral disc is particularly intolerant to rotational stress (4).

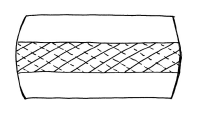

The fibers of the annulus (outer portion) of the intervertebral disc are arranged in layers, and each layer is crossed in opposite directions. During chronic rotational stress on the disc, half of the annular fibers become tense, and the other half become lax. Since rotational stress applied to the annulus is resisted by only half of the annular fibers, the disc is operating at only half strength. This increases the vulnerability of the disc to injury and degenerative disease.

Crossed Annular Fibers of the Intervertebral Disc

A common cause of chronic rotational stress on the L5-S1 intervertebral disc is postural pelvic unleveling. This was established in 1983 in a study where standing radiographs of the pelvis and lumbar spine were exposed in 288 consecutive patients with chronic low back pain and in 366 asymptomatic controls (11). Findings showed that 73% of the subjects assessed had meaningful inequality of a lower limb (>5 mm shortness), resulting in pelvic unleveling. The incidence of pelvic unleveling in LBP patients was significantly higher than in asymptomatic controls (more than twice as much).

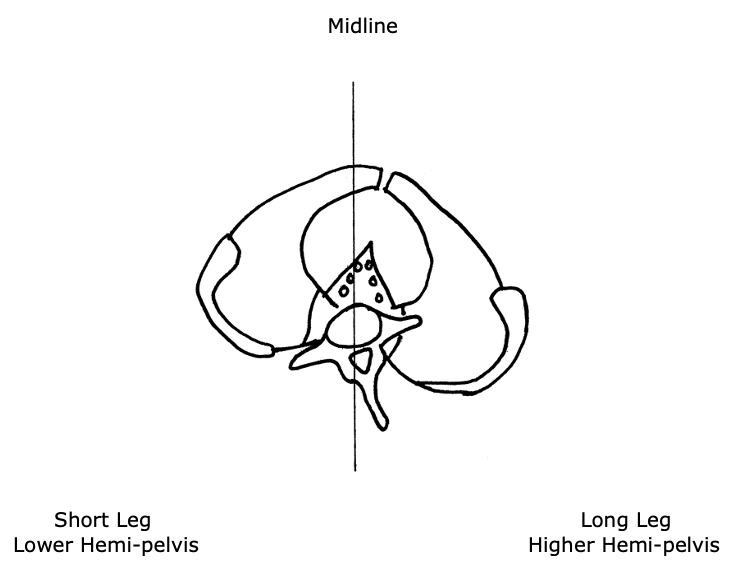

The counter-rotational stresses on the L5-S1 intervertebral disc:

Axial View From Above

- The L5 spinous process will rotate to the right of midline, towards the side of the long leg and/or higher hemi-pelvis. This causes a counterclockwise rotation of the L5-S1 intervertebral disc.

- The pubic symphysis and pelvis will also rotate to the right of midline, also towards the side of the long leg and/or higher hemi-pelvis. Because the pubic symphysis is in the anterior, this causes a clockwise rotation of the pelvis and sacrum, and a clockwise rotation of the L5-S1 intervertebral disc.

- This results in “significant” counter-rotational stresses, primarily at the L5-S1 intervertebral disc. The consequences of these counter- rotational stresses at the L5 disc are accelerated disc degeneration and degradation, back pain, and sciatica. Such aberrant biomechanics, especially when chronic and even when asymptomatic, predispose the intervertebral disc to injury and pain.

John Fitzgerald Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy was born in 1917. Growing up he suffered from a number of health problems, including scarlet fever, whooping cough, measles, chicken pox, an appendectomy, colitis, and a chronically bad back. His earliest low back pain diagnosis was attributed to a herniated disc injury sustained while playing football (12).

Prior to the United States involvement in World War II (December 7, 1941), Kennedy was medically disqualified from Officer Candidate School because of his bad back. Through perseverance, Kennedy eventually earned the rank of Lieutenant and was assigned as a commander of a patrol torpedo boat (PT-109) in the South Pacific.

While on patrol in the South Pacific, August 2, 1943, Kennedy’s PT-109 was struck and split in half by a much larger, fast-moving Japanese destroyer. Two of Kennedy’s crew were killed outright, and Kennedy’s already weak back was significantly reinjured (probably a second disc herniation).

In the aftermath of the destruction of his PT-109, Kennedy’s heroism to save his crew became legendary. His behavior became the topic of articles, books, movies, and political speeches. Kennedy was awarded a Purple Heart as well as the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for his leadership and courage.

The Secretary of the Navy stated:

“For extremely heroic conduct as Commanding Officer of Motor Torpedo Boat 109 following the collision and sinking of that vessel in the Pacific War area on August 1–2, 1943. Unmindful of personal danger, Lieutenant Kennedy unhesitatingly braved the difficulties and hazards of darkness to direct rescue operations, swimming many hours to secure aid and food after he had succeeded in getting his crew ashore. His outstanding courage, endurance and leadership contributed to the saving of several lives and were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

When Kennedy and his crew were eventually rescued on August 8, 1943, Kennedy was non-ambulatory. He was given a cane to help him up. That cane, along with a picture of Kennedy using it, can be seen in the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C. (13).

Despite his back injury, Kennedy only took a month off before returning to command another PT boat. As a consequence of his back injuries, Kennedy was relieved of command on November 18, 1941. He spent months at a military hospital recovering from his back injuries. Because of his low back physical disability, Kennedy was honorably discharged on March 1, 1945.

In 1946, Kennedy was elected to Congress. In 1952, Kennedy was elected to the Senate. During these years, Kennedy’s back problems continued to worsen (14).

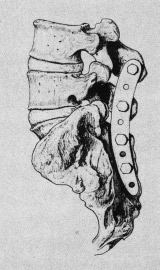

In 1954, Senator Kennedy underwent a spinal fusion operation (14):

This fusion operation resulted in chronic infection and the surgical wound was not healing. In February 1955, in yet another operation, the fusion hardware was surgically removed. Kennedy remained non-ambulatory through May of 1955. In desperation, Kennedy was referred to an internal medicine cardiologist from Cornell University, Janet Travell, MD.

Janet Travell

Janet Travell was born in New York in 1901. She died in 1997 at the age of 96. Both of her parents were physicians. In 1926, she received her medical degree from Cornell University Medical College in New York City, where she graduated at the head of her class. She was the first female to graduate from Cornell. In the first three decades of her professional career, she practiced cardiology while teaching pharmacology at Cornell. Her interest in musculoskeletal pain came about as a consequence of the neck, trunk, shoulder, and arm pains her cardiac patients suffered (15).

When Dr. Travell first saw Senator Kennedy in 1955, she had already developed a reputation for excellence in managing chronic musculoskeletal disorders (16, 17, 18, 19). Her experience and expertise led her to look to mechanical causes and/or contributors to Kennedy’s chronic disabling back problems.

Dr. Travell “discovered that one of [Senator] Kennedy’s legs was shorter than the other and made heel lifts for all of his left shoes to counter that additional source of stress on his back…. Dr. Travell had a workbench in her office and made lifts for both patients and family members. ‘One of the first things I did for him [Kennedy] was to institute a heel lift—a correction for the difference in leg length.’” (20)

At Dr. Travell’s direction, Senator Kennedy spent his 38th birthday in the hospital. Neurosurgeons T. Glenn Pait and Justin T. Dowdy note (14):

“In 1955, Kennedy was introduced to Dr. Janet Travell, a Cornell University pharmacologist and internal medicine specialist.”

“Dr. Travell promptly admitted Senator Kennedy to the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center to jump-start his rehabilitation program.”

“[Travell] introduced Kennedy to what would, in a few short years, become a symbol of his presidency—the rocking chair.”

“More importantly, it marks the end of his major back surgeries and a shift in focus toward muscular and environmental factors contributing to his back pain.”

“The emphasis regarding treatment of his back would move in a more cautious direction going forward, and notable functional restoration would be seen over the next few months.”

Importantly, Drs. Pait and Dowdy also note (14):

“In addition to the rocking chair, Travell made other changes, including providing Kennedy with a heel lift— raising the possibility of pelvic obliquity and leg-length discrepancy as a contributing factor in Kennedy’s low back pain.”

In 2003, Dr. Travell’s daughter wrote (15):

“Senator Kennedy received so much relief of pain from my mother’s medical treatments that he had ‘new hope for a life free from crutches if not from backache’.”

In 2003, James Bagg wrote this, pertaining to Dr. Travell (20):

“Jack Kennedy saw a great many physicians over the course of his short life, but one of them, according to his brother Bobby, enabled Jack to become President of the United States.”

Kennedy considered Travell to be a medical genius (15). When Kennedy was elected to the presidency of the United States, he asked Dr. Travell to be his personal White House Physician, becoming the first woman and one of the few civilians (non-military) to hold that post. After President Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, his successor, President Lyndon B. Johnson, asked Dr. Travell to stay on in the White House as his physician. A year and a half later, she resigned to return to private practice and to the position of Associate Clinical Professor of Medicine at George Washington University. She became Emeritus Clinical Professor of Medicine from 1970–1988 and Honorary Clinical Professor of Medicine from 1988 until her death in 1997. Dr. Travell remained professionally active until the end of her life, writing articles, giving lectures, and attending conferences.

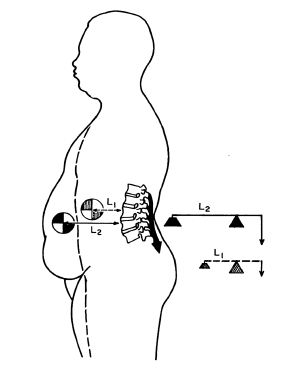

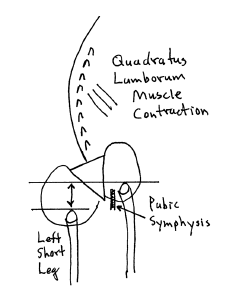

In her writings and books, Dr. Travell recognized that a common yet overlooked “perpetuating factor” for chronic discogenic back pain and counterbalancing muscular stress was a structural difference in the length of the lower limbs (21, 22, 23). It has been documented since 1946 that about 75% of people have legs of unequal lengths, and that about a third of people have leg length differences that contribute to chronic back pain. As a rule, the sacrum is lower on the side of the short leg (see drawing below). The spinal column initially tilts towards the short leg, then compensates back to the midline as a consequence of chronic contraction of the quadratus lumborum muscle (24).

Posterior to Anterior View From Behind

- The sacrum is lower on the side of the short leg (left in this drawing).

- The spinal column initially tilts towards the short leg, then compensates back to the midline as a consequence of contraction of the quadratus lumborum

- The lumbar spinous processes (posterior) rotate towards the long leg. The pubic symphysis (anterior) also rotates towards the long leg. The consequent counter-rotational forces abnormally stress the L5 intervertebral disc.

Dr. Travell noted that the solution was a proper heal lift, inserted into the shoe with the goal of leveling the pelvis and removing the counter-rotational stress of the L5 intervertebral disc. This intervention was included in her management of Senator Kennedy.

SUMMARY

The war heroism of Lieutenant Kennedy, his political importance as Congressman, Senator, and President of the United States, and the fact that the best of contemporary medical care failed to help his chronic back problems and disability, led to a profound change in the management of back pain. Janet Travell, a cardiologist with an interest in musculoskeletal pain syndromes, looked at then Senator Kennedy’s back from a mechanical perspective. Her care included the use of a rocking chair and the insertion of a heel lift to level his pelvis and remove chronic rotational stress to his L5 intervertebral disc. This approach would also relieve the chronic contraction of the counter-balancing muscles, markedly reducing fulcrum (disc) stress.

Travell’s approach worked, at least better than any other intervention, especially considering the tremendous damage and infections that had already been done by failed surgeries.

These and other mechanical interventions are common place, the rule, in chiropractic clinical practice. Over the decades, numerous additional studies continued to document the relationship between the anatomical short leg syndrome, pelvic unleveling, and chronic back pain (25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34).

REFERENCES

- White AA, Panjabi MM; Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine; Second Edition; Lippincott; 1990.

- Cailliet R; Soft Tissue Pain and Disability; 3rd Edition; FA Davis Company; 1996.

- Bowman K; Move Your DNA: Restore Your Health Through Natural Movement; Propriometrics Press; 2017.

- Kapandji IA; The Physiology of the Joints; Volume 3; The Trunk and the Vertebral Column; Churchill Livingstone; 1974.

- Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Moore C; The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults; Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey; Spine; December 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 23; pp. 1810–1816.

- Nachemson AL; The Lumbar Spine, An Orthopedic Challenge; Spine; Vol. 1; No. 1; March 1976; pp. 59-71.

- Mooney V; Where Is the Pain Coming From?; Spine; Vol. 12; No. 8; 1987; pp. 754-759.

- Kuslich S, Ulstrom C, Michael C; The Tissue Origin of Low Back Pain and Sciatica: A Report of Pain Response to Tissue Stimulation During Operations on the Lumbar Spine Using Local Anesthesia; Orthopedic Clinics of North America; Vol. 22; No. 2; April 1991; pp. 181-7.

- Izzo R, Popolizio T, D’Aprile P, Muto M; Spine Pain; European Journal of Radiology; May 2015; Vol. 84; pp. 746–756.

- Groh AMR, Fournier DE, Battie MC, Seguin CA; Innervation of the Human Intervertebral Disc: A Scoping Review; Pain Medicine; June 4, 2021; Vol. 22; No. 6; pp. 1281–1304.

- Friberg O; Clinical Symptoms and Biomechanics of Lumbar Spine and Hip Joint in Leg Length Inequality; Spine; September 1983; Vol. 8; No. 6; pp. 643-651.

- https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/life-of-john-f-kennedy

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/remembering-pt-109-63427209/

- Pait TG, Dowdy JT; John F. Kennedy’s Back: Chronic Pain, Failed Surgeries, and the Story of its Effects on His Life and Death; Journal of Neurosurgery Spine; September 2017; Vol. 27; No. 3; pp. 247-255.

- Wilson V; Janet G. Travell, MD: A Daughter’s Recollection; Texas Heart Institute Journal; 2003; Vol. 30; No. 1; pp. 8–12.

- pain-education.com/dr-travell.html; A Tribute to Dr. Janet Travell; accessed December 11, 2013.

- Lacayo R; How Sick Was J.F.K.?; TIME; November 24, 2002.

- Altman LK, Purdum TS; In J.F.K. File, Hidden Illness, Pain and Pills; The New York Times; November 17, 2002.

- Dallek R; The Medical Ordeals of JFK; The Atlantic; December 2002.

- Bagg JE; The President’s Physician; Texas Heart Institute Journal; 2003; 30; No. 1; pp. 1–2.

- Travell J, Simons D; Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction, the Trigger Point Manual; New York; Williams & Wilkins; 1983.

- Travell J, Simons D; Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction, the Trigger Point Manual: THE LOWER EXTREMITIES; New York; Williams & Wilkins; 1992.

- Simons D, Travell J; Travell & Simons’, Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction, the Trigger Point Manual: Volume 1, Upper Half of Body; Baltimore; Williams & Wilkins; 1999.

- Rush WA, Steiner HA; A Study of Lower Extremity Length Inequality; American Journal of Roentgenology and Radium Therapy; November 1946; Vol. 51; No. 5; pp. 616-623.

- Sicuranza B, Richards J, Tisdall L; The Short Leg Syndrome in Obstetrics and Gynecology; American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology; May 15, 1970; Vol. 107; No. 2; pp. 217-219.

- Giles LG, Taylor JR; Low-back Pain Associated with Leg Length Inequality; Spine; 1981 Sep-Oct; Vol. 6; No. 5; pp. 510-251.

- Friberg O; Clinical Symptoms and Biomechanics of Lumbar Spine and Hip Joint in Leg Length Inequality; Spine; September 1983; Vol. 8; No. 6; pp. 643-651.

- Gofton JP; Persistent Low Back Pain and Leg Length Disparity; Journal of Rheumatology; August 1985; Vol. 12; No. 4; pp. 747-750.

- Helliwell M; Leg Length Inequality and Low Back Pain; The Practitioner; May 1985; Vol. 229; pp. 483-485.

- Defrin R, Benyamin SB, Dov Aldubi R, Pick CG; Conservative Correction of Leg-Length Discrepancies of 10 mm or Less for the Relief of Chronic Low Back Pain; Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation; November 2005; Vol. 86; No. 11; pp. 2075-2080.

- Golightly YM, Tate JJ, Burns CB, Gross MT; Changes in Pain and Disability Secondary to Shoe Lift Intervention in Subjects With Limb Length Inequality and Chronic Low Back Pain; Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy; Vol. 37; No. 7; July 2007; pp. 380-388.

- Balik SM, Kanat A, Erkut A, Ozdemir B, Batcik OE; Inequality in Leg Length is Important for the Understanding of the Pathophysiology of Lumbar Disc Herniation; Journal of Craniovertebral Junction; Spine; April-June 2016; Vol. 7; No. 2; pp. 87-90.

- Cambron JA, Dexheimer JM, Duarte M, Freels S; Shoe Orthotics for the Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial; Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation; September, 2017; Vol. 98; No. 9; pp. 1752-1762.

- Sheha ED; Steinhaus ME; Kim HJ; Cunningham ME; Fragomen AT; Rozbruch SR; Leg-Length Discrepancy, Functional Scoliosis, and Low Back Pain; Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery Reviews; August 8, 2018; Vol. 6; No. 8; pp. e6.

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C.. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”