Dizziness and the Neck

All perceptions occur in the brain, specifically in a region of the brain called the cerebral cortex (cortical brain) (1). These perceptions include sight (vision), sound (hearing), hot/cold (temperature), taste, smell, pressure, vibration, positional sense, pain, and more. The cortical perception in this discussion will be referred to as dizziness. Dizziness is a cortical perception occurring in the brain.

“Vertigo” is a term primarily used by health care providers. It is a condition in which somebody feels a sensation of whirling or tilting that causes a loss of balance. Health care providers often use the term vertigo when patients describe sensations of giddiness, unsteadiness, lightheadedness, disorientation, and even perhaps “twisties” (a recently familiar term applied to some gymnasts during the 2021 summer Olympics). The most common lay and professional term for vertigo is dizziness. We will primarily use the word dizziness to encompass these related cortical brain perceptions throughout this presentation.

Certain brain injuries or strokes can cause the perception of dizziness. However, more commonly, people with dizziness do not have any injury to their brain. Rather, the dizziness perception part of their brain is being sent an electrical signal by a “quarterback.”

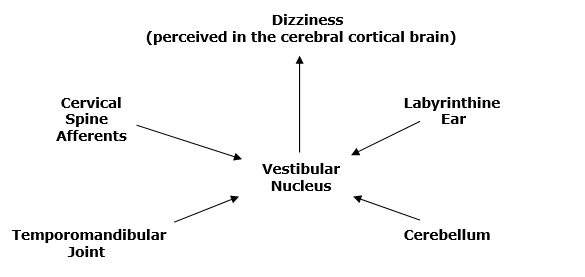

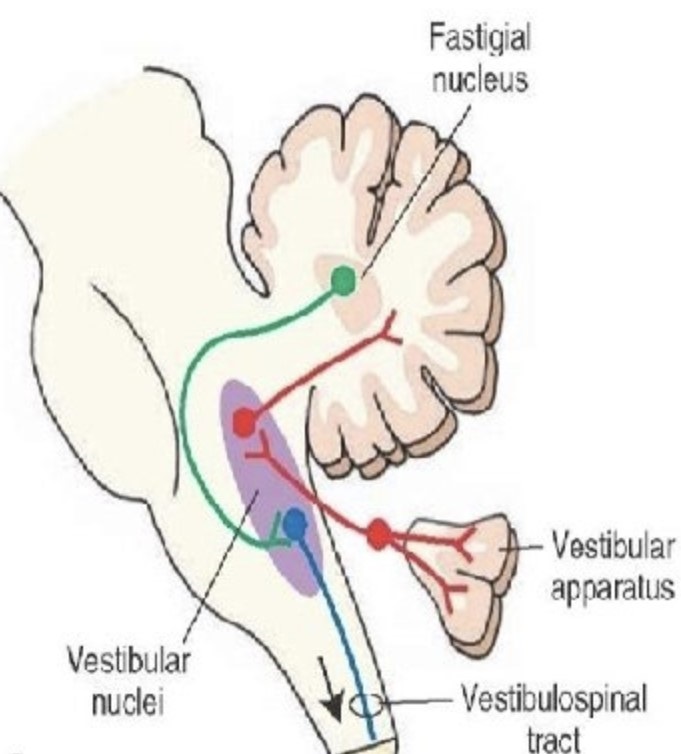

The “quarterback” for dizziness is an area in the lower part (medulla oblongata) of the brainstem, in a tight collection of nerve cells termed the vestibular nuclei (vestibular nucleus is the singular). The vestibular nucleus sends an electrical signal to the cerebral cortex via neurons for the cortical perception of dizziness.

A number of players can send the electrical signal to the quarterback (vestibular nucleus) before the electrical signal is sent to the cortical brain. As noted in the graphic above, these other players include:

- Labyrinthine Inner Ear (2)

- Cerebellum (3)

- Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) (4, 5, 6)

- Neck (cervical spine) afferents (7)

The primary input for the present discussion is that dizziness is being caused by the sensory nerves (afferents) that arise in the neck (cervical spine). The management of such dizziness is to the neck, including spinal manipulation. Many health care providers are not aware that dizziness can be caused by mechanical problems of the cervical spine.

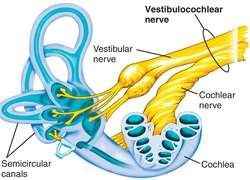

Relevant to the understanding of dizziness is the neurological anatomy of he ear apparatus. The name of the nerve that innervates the ear is the vestibulocochlear nerve, also known as Cranial Nerve VIII. The vestibulocochlear nerve has two distinct components (8, 9):

The Cochlear component:

- The Cochlear component functions for the perception of sound (hearing).

- The Vestibular component:

- The Vestibular component functions for the perception of balance, coordination, posture, space awareness, stability, etc.

As a consequence of this neuroanatomy, most health care professionals and lay persons default to the labyrinthine (inner) ear as the prime driver of dizziness. The provider initially believes that source of the adverse afferent that is causing a patient’s dizziness is the inner ear and/or the vestibular component of the vestibulocochlear nerve. The health care provider will look into the ear canal with an otoscope, and perform a handful of related diagnostic tests. Common differential diagnostics include inner ear infections, inflammation, injury, interrupted blood flow, tumor, etc. Often, these tests are nonrevealing.

The first study to link problems in the cervical spine to vertigo was published in 1950. Today (August 2021), a search of the National Library of Medicine with PubMed, using the words “cervical vertigo” locates 3,743 citations.

Review of Pertinent Studies

In 1955, a study was published in the journal Lancet, titled (10):

Cervical Vertigo

The authors state that “the neck plays a larger part in the mechanism of vertigo than is generally thought.” They make a case for cervical vertigo being linked to cervical spine spondylosis and/or to an injury to a spondylotic cervical spine. They state that classically, the patient will have cervical spine symptoms (primarily pain), and objective findings, (especially stiffness). They note that problems in the upper cervical spine are most commonly to be associated with vertigo.

•••

In 1983, the journal Manual Medicine published a study titled (11):

Disequilibrium, Caused by a Functional Disturbance

of the Upper Cervical Spine:

Clinical Aspects and Differential Diagnosis

The author notes that disequilibrium may be “caused by a functional disturbance of the upper cervical spine,” as a consequence of the importance of the proprioceptors at levels C1-C3 level. About 50% of the cervical proprioceptors are found in the joint capsules of C1-C3. The author also notes that the therapy of choice for the functional disturbance of the upper cervical spine is manual therapy, but caution that vascular involvement (vertebral artery) should be ruled out:

Proprioceptive Cervical Nystagmus v. Vascular Cervical Nystagmus

| Proprioceptive | Vascular |

| Occurs during body rotation | Normally only with maximal neck rotation |

| No latent period | Yes latent period, from a few seconds to 50 seconds |

| Always noted in different directions of cervical motion | Usually only in one direction, the direction that increases vertebral artery stenosis |

•••

In her 1996 chapter titled “Posttraumatic Vertigo”, Dr. Linda Luxon notes that this vertigo can be explained by “disruption of cervical proprioceptive input.” (12) Dr. Luxon notes that dysfunctional upper cervical spinal joints and their capsules can alter the proprioceptive afferent input to the vestibular nucleus resulting in the symptoms of vertigo. Treatment would be to improve the mechanical function of these joints.

•••

In 1998, an article appeared in the European Spine Journal titled (13):

Vertigo in Patients with Cervical Spine Dysfunction

The authors defined “dysfunction” as a reversible, functional restriction of motion of an individual spinal segment or as articular malfunction presenting with hypomobility. They also note that upper cervical spine dysfunctions can cause vertigo as a consequence of upper cervical spine receptors communicating with the vestibular nuclei. They explain vertigo exists as a consequence of disturbances of proprioception from the neck.

In this study, the authors present the management and clinical outcome for 50 patients suffering from suspected cervical vertigo. The cervical spine dysfunctions were treated with mobilization and manipulative techniques. The authors concluded that cervical spine dysfunction, especially of the upper cervical spine, is an important cause of vertigo, and that manual/manipulative therapy is the most promising management for these patients.

•••

In 2001, an article appeared in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychology titled (14):

Cervical Vertigo

This article reviews the theoretical basis for cervical vertigo. These authors note that proprioceptive input from the neck participates in the coordination of eye, head, and body posture as well as spatial orientation, and this is the basis of cervical vertigo. Cervical vertigo is when the suspected mechanism is proprioceptive.

Degenerative or traumatic changes of the cervical spine can induce altered cervical sensory input causing vertigo. Altered cervical proprioceptive input to the vestibular nucleus may result in disorientation and postural imbalance. They state:

“If cervical vertigo exists, appropriate management is the same as that for the cervical pain syndrome.”

•••

In 2002, an article appeared in the Journal of Whiplash & Related Disorders, titled (15):

A Cross-Sectional Study of the Association Between Pain and Disability

in Neck Pain Patients with Dizziness of Suspected Cervical Origin

The authors evaluated 180 consecutive neck pain patients for the presence of cervical vertigo. They note that “increasing evidence suggests that dizziness and vertigo may arise from dysfunctional cervical spine structures.” Cervicogenic dizziness may result fromdisturbed sensory information from dysfunctional joint and neck mechanoreceptors (proprioceptors). They state:

“Dysfunction or trauma to connective tissues such as cervical muscles and ligaments rich in proprioceptive receptors (mechanoreceptors) may lead to sensory impairment.”

“Emerging evidence suggests that dizziness and vertigo may commonly arise from dysfunctional cervical spine structures such as joint and neck mechanoreceptors, particularly from trauma.”

The authors note that dizzy patients also describe their symptoms with “lightheadedness, seasickness, instability.” The basic model presented in this article is that trauma causes “dysfunctional cervical spine structures” resulting in altered “joint and neck mechanoreceptor” function, causing both pain and dizziness.

•••

In 2003, a study appeared in the Journal of Rehabilitative Medicine titled (16):

Dizziness and Unsteadiness Following Whiplash Injury

These authors note that dizziness and/or unsteadiness are common symptoms of chronic whiplash-associated disorders, and probably secondary to cervical spine joint injury. Their study assessed 102 whiplash subjects and 44 control subjects. The authors concluded:

“Cervical mechanoreceptor dysfunction is a likely cause of dizziness in whiplash-associated disorder.”

Dizziness of cervical origin “originates from abnormal afferent activity from the extensive neck muscle and joint proprioceptors, which converges in the central nervous system with vestibular and visual signals, confusing the postural control system.”

These authors note that the most common words used by patients to describe their symptoms were “lightheaded”, “unsteady” and “off-balance”. Other descriptions were clumsy, giddy, imbalance, motion sickness, falling/veering to one side, imbalance in the dark, vision jiggle (disturbance), faint feeling, might fall. Unsteadiness was the most common description, being stated by 90% of the subjects.

The authors emphasize the importance of cervical spine mechanoreceptor dysfunction in causing vertigo, dizziness, and unsteadiness.

•••

In 2005, a study appeared in the journal Manual Therapy titled (17):

Manual Therapy Treatment of Cervicogenic Dizziness:

A Systematic Review

The authors note, “in some people the cause of their dizziness is pathology or dysfunction of upper cervical vertebral segments that can be treated with manual therapy.” After reviewing the literature on the topic, they state:

“A consistent finding was that all studies had a positive result with significant improvement in symptoms and signs of dizziness after manual therapy treatment.”

“Manual therapy treatment of cervicogenic dizziness was obtained indicating it should be considered in the management of patients with this disorder.”

This same group has continued to publish clinical studies documenting the validity of manual therapy in the treatment of these patients (18, 19, 20).

•••

In 2015, an article appeared in the journal Pain Physician titled (21):

Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Cervical Vertigo

The authors detail a syndrome they call “Proprioceptive Cervical Vertigo,” in which abnormal afferent input to the vestibular nucleus from damaged joint receptors in the upper cervical region alter vestibular function resulting in cervical vertigo. They state:

There are “close connections between the cervical dorsal roots and the vestibular nuclei with the neck receptors (such as proprioceptors and joint receptors), which played a role in eye-hand coordination, perception of balance, and postural adjustments. With such close connections between the cervical receptors and balance function, it is understandable that traumatic, degenerative, inflammatory, or mechanical derangements of the cervical spine can affect the mechanoreceptor system and give rise to vertigo.”

“Evidence leads to the current theory that cervical vertigo results from abnormal input into the vestibular nuclei from the proprioceptors of the upper cervical region.”

“Manual therapy is recommended for treatment of proprioceptive cervical vertigo.”

“Manual therapy is effective for cervical vertigo.”

These authors also note that cervical vertigo patients usually have pain in the back of the neck and occipital region, sometimes accompanied by neck stiffness. Cervical vertigo is often increased with neck movements or neck pain and decreased with interventions that relieve neck pain. Since cervical vertigo originates from proprioceptive dysfunction of the upper cervical spine, treatment should be to the upper cervical spine. Chiropractic and other manual spinal therapies have been shown to be effective in treating cervical vertigo, typically with around 80% acceptable clinical outcomes.

•••

In 2020, an article appeared in the Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation, titled (22):

Upper Cervical Spine Dysfunction and Dizziness

The purpose of this study was to investigate the association between the upper part of the cervical spine and dizziness. The author notes that dizziness affects 20%–30% of the general population. He also notes that cervicogenic dizziness may account for as much as 90% of vertigo cases. He indicates that when vestibular and cardiovascular pathologies have been ruled out as causes of dizziness, “cervicogenic dizziness should be suspected.”

Problems that occur in the ligaments or muscles of the upper cervical spine can cause confusion in proprioception and convey misinformation to the vestibular nucleus. The proprioceptive system is extremely well developed in the cervical zygapophyseal joints, and 50% of all cervical proprioceptors are located in the joint capsules from C1–C3.

Damaged receptors in the upper cervical spine relay abnormal signals to the vestibular nucleus, and result in cervicogenic vertigo. The author states:

“The sensory mismatch of cervicogenic dizziness may be solved by applying manual therapy to increase stimulation of proprioceptors to the upper cervical spine.”

•••

In 2021, an article appeared in the World Journal of Clinical Cases, titled (23):

Cervical Intervertebral Disc Degeneration and Dizziness

This study represents a comprehensive review of the literature on the topic of cervicogenic dizziness. The authors note that dizziness is a common complaint encountered in clinical practice, and that cervicogenic dizziness is considered to be one of the most common etiologies of dizziness. Patients with chronic neck pain often suffer from dizziness. The authors state:

“Abnormal cervical proprioceptive inputs from the mechanoreceptors are transmitted to the central nervous system, resulting in sensory mismatches with vestibular and visual information and leads to dizziness.”

Disequilibrium originates from “abnormal afferent activity arising in the neck.”

“Neck pain and dizziness are two common concomitant symptoms of cervical degenerative disease.”

“Clinical studies have found that patients with cervical degenerative disease is usually accompanied by dizziness.”

“Cervical degenerative disease is the most common cervical spine disorder in humans,” and that 50%-65% of patients with cervical spondylosis have dizziness.

Evidence from the studies “suggests that cervicogenic dizziness is caused by cervical disc degeneration.”

The authors present a discussion on the importance of symmetrical proprioceptive input from the cervical spine to the vestibular nucleus in preventing cervicogenic vertigo. This discussion is particularly important to the chiropractic concepts of symmetry of alignment and symmetry of movement. The authors state:

“Integration of symmetrical inputs from these afferent systems is essential for normal orientation and balance, and any dysfunction or asymmetry of afferent inputs in these sensory organs can lead to imbalance or dizziness.”

The authors note that the management of dizziness is the same as for neck pain, namely conservative manual interventions to promote symmetry of alignment and movement. The authors conclude that degenerative cervical discs do not always cause neck pain; degenerative cervical discs do not always cause dizziness; yet, there is “sufficient evidence that degenerated cervical discs are a source of dizziness.”

SUMMARY

Hundreds, perhaps thousands of studies have established that mechanical dysfunction of the cervical spine can cause the sensation of dizziness. Cervical spine mechanoreceptors/proprioceptors communicate with the vestibular nucleus as a portion of our human upright balance mechanisms.

The mechanoreceptor/proprioceptor dysfunction of the cervical spine is determined by those trained in manual diagnostics, static palpation, motion palpation, and/or radiology. These skills are emphasized in chiropractic college education and in post-graduate training courses. Appropriate and safe treatment of upper cervical spine mechanical problems is a skill that is at the core of chiropractic training. Chiropractors are exceptionally trained in the diagnosis and treatment of cervical vertigo.

REFERENCES

- Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM; Principles of Neuroscience; Fourth Edition; McGraw-Hill; 2000.

- Epley JM; The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo; Otolaryngology Head Neck Surgery; September 1992; Vol. 107; No. 3; pp. 399-404.

- Baloh R, Honrubia V; Clinical Neurophysiology of the Vestibular System; Third edition; Oxford University Press; 2001.

- Jordan P, Ramon Y; Nystagmus and Vertigo Produced by Mechanical Irritation of the Temporomandibular Joint-space; Journal of Laryngology and Otology; August 1965; Vol. 79; pp. 744-748.

- Morgan DH; Temporomandibular Joint Surgery. Correction of Pain, Tinnitus, and Vertigo; Dental Radiography and Photography; 1973; Vol. 46; No. 2; pp. 27-39.

- Wright EF; Otologic Symptom Improvement Through TMD Therapy; Quintessence International; October 2007; Vol. 38; No. 9; pp. e564-571.

- de Jong PT, de Jong JM, Cohen B, Jongkees LB; Ataxia and nystagmus induced by injection of local anesthetics in the Neck; Annals of Neurology; March 1977; Vol. 1; No. 3; pp. 240-246.

- Wilson-Pauwels L, Stewart PA, Akesson EJ; Autonomic Nerves: Basic Science, Clinical Aspects, Case Studies; BC Decker, Inc.; 1997.

- Wilson-Pauwels L, Akesson EJ, Stewart PA, Spacey SD; Cranial Nerves in Health and Disease; Second Edition; BC Decker, Inc.; 2002.

- Ryan GM, Cope S, Leeds MD; Cervical Vertigo; Lancet; December 31, 1955; Vol. 269; No. 6905; pp. 1355-1358.

- Hulse M; Disequilibrium, Caused by a Functional Disturbance of the Upper Cervical Spine: Clinical Aspects and Differential Diagnosis; Manual Medicine 1983; No. 1; pp. 18-23.

- Luxon L; “Posttraumatic Vertigo” in Disorders of the Vestibular System, edited by Robert W. Baloh and G. Michael Halmagyi; Oxford University Press; 1996.

- Galm R, Rittmeister M, Schmitt E; Vertigo in patients with cervical spine dysfunction; European Spine Journal; 1998; Vol. 7; No. 1; pp. 55-58.

- Brandt T, Bronstein M; Cervical Vertigo; Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry; July 2001; Vol. 71; No. 1, pp. 8-12.

- Humphreys KM, Bolton J, Peterson C, Wood A; A Cross-Sectional Study of the Association Between Pain and Disability in Neck Pain Patients with Dizziness of Suspected Cervical Origin; Journal of Whiplash & Related Disorders; 2002; Vol. 1; No. 2; pp. 63-73.

- Treleaven J, Jull G, Sterling M; Dizziness and Unsteadiness Following Whiplash Injury: Characteristic Features and Relationship with Cervical Joint position Error; Journal of Rehabilitative Medicine; January 2003; Vol. 35; No. 1; pp. 36–43.

- Reid SA, Rivett DA; Manual therapy treatment of cervicogenic dizziness: a systematic review; Manual Therapy; February 2005; Vol. 10; No. 1; pp. 4-13.

- Reid SA, Rivett DA, Katekar MG, Callister R;Sustained natural apophyseal glides (SNAGs) are an effective treatment for cervicogenic dizziness; Manual Therapy; August 2008; Vol. 13; No. 4; pp. 357-366.

- Reid SA, Rivett DA, Katekar MG, Callister R; Comparison of mulligan sustained natural apophyseal glides and maitland mobilizations for treatment of cervicogenic dizziness: a randomized controlled trial; Physical Therapy; April 2014; Vol. 94; No. 4; pp. 466-476.

- Reid SA, Callister R, Snodgrass SJ, Katekar MG, Rivett DA;Manual therapy for cervicogenic dizziness: Long-term outcomes of a randomised trial; Manual Therapy; February 2015; Vol. 20; No. 1; pp. 148-156.

- Li Y, Baogan Peng B; Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Cervical Vertigo; Pain Physician; July/August 2015; Vol. 18; pp. E583-E595.

- Sung YH; Upper Cervical Spine Dysfunction and Dizziness; Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation; October 27, 2020; Vol. 16; No. 5; pp. 385-391.

- Liu TH, Liu YQ, Peng BG; Cervical Intervertebral Disc Degeneration and Dizziness; World Journal of Clinical Cases; March 26, 2021; Vol. 9; No. 9; pp. 2146-2152.

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C.. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”